Kagan's Articles - FREE Kagan Articles

Articles by Dr. Vern Minor

The Rigor/Relevance Framework: Where Kagan Structures Fit In

Special Article

Kagan Connections—The Rigor/Relevance Framework

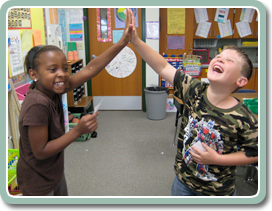

Let's analyze what's going on here to see the power of Kagan Structures. First, the curriculum is made more relevant. Instead of a math problem that looks like: $45 x 30% = ?, the teacher converts the problem into a real-world scenario that captures students' interest: "The video game store is having a 30% sale on your favorite game that usually sells for $45. How much will it cost you?" Making a math problem more real-world is not unique to Kagan Structures. But look what happens next. Instead of students individually solving the problems on a worksheet, students solve the problem then put their heads together with teammates to reach consensus on the answer. They show their teammates their answers. They check for consensus. If someone has an incorrect answer, they disagree politely. They negotiate understanding. They explain the problem. They tutor each other. The teacher randomly selects one teammate to share the team's answer to hold everyone accountable for participating. When correct, the team celebrates their selected teammate with a high-five. Notice too, students' re-orientation from independent learners to being members of a team, on the same side, helping each other, and hoping for the success of teammates. The curriculum is no different than in the classroom next door; it's multiplying percents. But the cooperative and interactive instructional strategies makes the process so much richer. In addition to learning a math skill, students practice their social skills, thinking skills, communication skills, and teamwork skills (sharing, comparing, negotiating meaning, tutoring, appreciating). By choosing Kagan instructional strategies we make education a richer preparation for essential life skills. Is it surprising to learn that cooperative learning instructional strategies are superior to traditional alternatives for teaching academic content as well as social skills?

A critic may concede that the Kagan model is an elegant solution for simultaneously delivering an academic, social, and cognitive curriculum. Further, the critic may concur that this broader curriculum—one that includes a social, and cognitive dimension in addition to the academic dimension—is more "relevant" than a strictly academic curriculum. However, the critic might point out that our example is of a predictable learning application. How is that preparing students for the highest degree of application in the Application Model—real-world application to unpredictable situations?

Social interaction carries a degree of unpredictability. With social interaction, you never know in advance the direction it will take. That's part of the reason students love to work in teams. There is a novelty factor when interacting with others. But the point is well taken—much of education, including our example, doesn't prepare students for unpredictable outcomes. Education often focuses narrowly on pre-defined objectives where the parameters are controlled and all students are working toward the same solution. We make a distinction between high-consensus and low-consensus learning. High-consensus learning is when given a problem or challenge, most people will come up with the same answer or solution. Low-consenus, in contrast, is where people may come up with solutions that are very different.

The variety of structures in the Kagan Model equip teachers with a wide range of cooperative structures for a wide spectrum of teaching objectives. There are great structures, like Numbered Heads Together, Sage–N–Scribe, and RallyCoach for teaching high-consensus, need-to-know facts and skills. But Kagan also offers structures for teaching divergent and creative thinking such as Timed–Pair–Share, Team Statements, and Agreement Circles. With these structures, our goal is to develop critical and creative thought, the exact processes used in the real-world in unpredictable scenarios.

With the Kagan model we have a number of options to enhance students' ability to apply their knowledge to unpredictable outcomes. But how do we make learning more real-world? What do we do if we want to move right on the Application Model and move away from pre-defined competencies? Instead of transmitting knowledge, how do we get students to apply their learning in creative ways to solve real-world problems? How do we create low-consensus content? That's where team projects and presentations come in!

Project Structures.

Cooperative projects and presentations are Kagan's answer to open-ended, creative endeavors that not only require students to integrate skills across disciplines, but also to pool strengths and knowledge across teammates—just as we do in the real world.

Team Projects, one of the most utilitarian of the project structures, starts with a challenge. To integrate academic learning in astronomy, the team's challenge may be to build a model of the solar system. To apply social studies learning, the team's challenge may be to write and perform a play about the gold rush. To apply language arts knowledge, the team's challenge may be to write a creative story. The more real-world the challenge, the more practice we provide our students in applying their knowledge to scenarios they'll likely encounter beyond the classroom.

Professions are a wonderful source for project ideas because there is nothing more real-world than the real projects professionals do. For example, a graphic designer creates a brochure. Creating the brochure requires the application of skills in math, language arts, visual arts, technology. Students can create a brochure on a state they are studying. Take another profession: Advertising. An advertising team may produce a commercial to sell a product. Teams in the classroom can make a commercial to sell their position on a social issue. A final example: Computer programmers write programs. Students can design a computer program to teach a math skill. Each of these projects is very real world, integrates skills across subject matters, and leverages teamwork.

But the project itself is just part of the story. The other parts include presenting the project to classmates and learning about their projects as well. Oftentimes, students acquire as much knowledge through the projects of others as they do their own. This information sharing process is also closely aligned to real-world practices. For examples, political candidates must share their platforms, scientists share their discoveries to colleagues, computer developers share their latest technology at developer conferences.

In our book, Kagan Cooperative Learning7, we have a chapter dedicated to cooperative projects and presentations. There, we outline the Kagan approach to cooperative projects. Some of the best Kagan Project and Presentation Structures include:

Early forms of cooperative learning were frequently project-based. Co-op Co-op8, Group Investigation, Partners, and Co-op Jigsaw were cooperative learning staples. Interestingly, with the emphasis on test scores and content mastery many of these powerful forms of investigations fell from favor. With a resurgence of interest in project learning and real-world applications, these designs are all great structures for constructing meaning, working in teams, and applying and presenting knowledge in highly creative ways.

Increasing Rigor, Increasing Relevance

Kagan Structures is not a single instructional strategy. Kagan Structures have evolved into a wide range of teaching methods that engage students. There are more than 200+ Structures for teaching. There are so many structures because educators have so many teaching objectives. There are simple structures to promote basic content mastery. There are structures used to develop very specific thinking skills. There are structures for brainstorming, structures for making decisions, structures for sharing information. No single instructional strategy can do it all! That's why we have developed so many structures that respect research-based principles for cooperation and learning. So if the question is: Is there a structure for making learning more rigorous and more relevant? The answer is: Yes! There's a structure for that… actually, quite a few.

Reference

1. International Center for Leadership in Education. Rigor/Relevance Framework®

www.leadered.com/rrr.html. Retrieved August, 2011.

2. International Center for Leadership in Education. Rigor/Relevance Framework® PDF www.leadered.com/pdf/R&Rframework.pdf. Retrieved August, 2011.

3. Kagan, Spencer. "Rethinking Thinking — Does Bloom's Taxonomy Align with Brain Science?" San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing, Kagan Online Magazine.

4. Kagan, Spencer. "Kagan Structures for Thinking Skills." San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing, Kagan Online Magazine, Fall 2003.

5. National Association of Colleges and Employees. Job Outlook 2004. Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employees, 2004.

6. Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than I.Q. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1995.